The 100 Most Powerful People for the 80’s

With the exceptions of Ted Turner and a few politicians, nobody who has power or is seeking it wants to say so. It’s unseemly. When people learned that NEXT was planning to cite them for their likely roles in shaping this country’s future, their reactions ranged from “I just work here” to a disingenuous “Do you really think I’ll have that much power?” Even the President of the United States customarily grumps about the growing power of Congress, the press and the special-interest groups.

So who’s really running things around here? The answer seems to be: many people. Just as the country cannot expect another Churchill or de Caulle on the international scene, it also should not look for a dominating individual at home. Power will be scattered. A kind of decolonization is taking place domestically as well as internationally. There are now 163 nations in the world instead of 40, and at home there are countless groups struggling for power formerly held by a few.

All this is not necessarily bad news. The people leading the various struggles may be less well known and individually less powerful than their predecessors, but they suggest that this country is in for a lively future. Even when they work in traditional organizations, the new leaders are hardly plodding or tradition-bound, and their approaches to power are often strikingly original. A Tom Wilhite can go from Keswick, Iowa (population 300), to running Walt Disney’s film operation at the age of 28. A Lewis Lehrman can build one of the world’s largest drugstore chains, then chuck it all at age 35 to form his own think tank. These flexible, unpredictable people sometimes seem to lead nine lives and to have an influence in each of them.

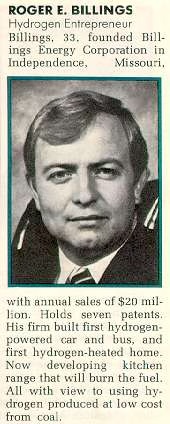

Roger Billings’ Profile

Talking with them produced two somewhat contradictory impressions about the future of power in the United States. First, smaller and even more specialized interest groups will proliferate; they will be adept at marshaling their supporters for action. Second, there will be an increasing concentration of power in America’s most central institution, the corporation.

Several trends will decentralize power in the years ahead:

• Local and regional issues will attract more world-beaters and earth-shakers. When John F. Kennedy had to choose between running for Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts or the United States House of Representatives, he remarked that he didn’t want to spend his life haggling over sewerage contracts—and headed for Washington. Over the next few years, more politicians are likely to opt for the sewerage contracts because of the inconstancy of political power in Washington, residual bad feeling over Watergate, local chauvinism (expressed not just as a love for home but as an unwillingness to submit to such centers of power as New York, Washington and Los Angeles) and, finally, the satisfaction of being a big fish in a small pond. After four years in Washington, Jimmy Carter may not be sure of what he accomplished. But Joe Riley Jr., Mayor of Charleston. South Carolina, knows that he brought the Spoleto Festival—and $24 million in tourism in a single two-week period—to what was once ridiculed as the “Sahara of the Ozarks.” Says Margaret Hance, the Mayor of Phoenix, “Cities are the jurisdiction closest to the people . . . the rewards and punishments are the swiftest and the surest. I don’t feel that going to the Senate, for example, is necessarily an advancement.”

The competition for local and regional office is becoming at times almost comically intense. In New Jersey, with the election still six months off, at least 18 people have declared themselves gubernatorial candidates. At the state’s big Democratic fund-raising dinner during last year’s Presidential campaign, the chairman asked, “Will all those who aren’t candidates for governor please stand up?” Nobody stood.

President Reagan, the self-described “Sagebrush Rebel,” will foster regionalism if, as promised, he turns back power from the Federal Government. A struggle will then be likely between the cities—which have long enjoyed a special and remunerative relationship with Federal grant-makers—and the states, led by Lamar Alexander, Governor of Tennessee, who argues that past Presidents have reduced them to little more than “administrative agents.

•Despite efforts at forming new coalitions, the generation between 20 and 40 years of age will remain politically diverse; different groups will go different ways. But those groups are showing sophistication in exploiting an unusual array of politicaltools to further their diverse ends. They will change the way people and corporations behave. Some examples: The Moral Majority unleashed a direct-mail attack to talk Warner-Lambert out of sponsoring a television show it found unsuitable. A Missouri union, rather than rouse opposition with a television ad campaign, used directmail to get its partisans out to defeat a right-to-work law. Wisconsin activists pushed through a law enabling a citizens board that was monitoring the utility company to use the utility company’s monthly bills as a fund-raising vehicle. Finally, in one of the more imaginative variations on the political poll, Douglas Schoen of New York overcame Venezuela’s high illiteracy rate and predicted his client’s narrow victory in the presidential race through a poll using flash cards coded with colors and political party symbols.

Sometime later in this decade, cable television, two-way computer communication and user-activated information distribution systems may rejigger the whole scheme of power in this country. How will it affect the networks if there are suddenly 140 television stations in Atlanta? How will it change Yale or Stanford if their entire libraries become available at the push of a button to a dropout in Dubuque?

The possibility is that the familiar centers of power will become less important, and peripheral areas, which are often more daring and experimental, will regain their attraction. The new technology will encourage people like David Gockley, who is trying to Americanize and popularize opera—not from Lincoln Center but from Houston and some of the sleepier towns of the Southwest. And the people who will wield the technology may not be just Atlanta’s Ted Turner or Boston’s Bob Bennett, but a hundred Turners ind Bennetts in a hundred once-sleepy communities.

Here, however, is the contradiction: While power is being dispersed to peripheral areas and organizations, it will at the same time probably become more concentrated in large corporations. The country elected Ronald Reagan not just to whittle away at the Federal bureaucracy and turn back its power, but also to unfetter overregulated industries and stimulate corporate investment in new plants. The mandate was not just anti-Government, but pro-business.

How the Reagan Administration will carry out that mandate has already been widely discussed, and the reactions are predictable. Herb Schmertz, vice president of Mobil Oil, argues that the change will promote “individual freedom” by getting Government off everyone’s back. And while he agrees that power will flow back to the corporations, he says that it won’t be “concentrated in any particular corporation.” Ralph Nader, on the other hand, argues that the executive and legislative branches of Government will become “extraordinary prisoners” of corporations, to the detriment of workers, consumers, motorists and the environment.

The Reagan White House is deliberately corporate not just in substance but in style and structure, and that may provide a model that furthers corporate power. “My guess is that an increasing percentage of college presidents will be business executives,” says Robert LeKachman, professor of economics at Lehman College in the City University of New York. “And I suspect that an increasing percentage of new union presidents are going to be managerial types. Because it’s unwise ever to underrate the sheer demonstration effect of success in capturing the White House.”

Even in such unlikely precincts as Harvard (where Derek Bok, the president, still wants to get the university into the genetic engineering business) and the University of California (where Herbert Boyer of Genentech remains a professor), the notion is regaining acceptability that the business of America is, in fact, business.

The corporate model of power and authority may be gaining importance simply because that’s where the money is. LeKachman argues that the continuing influence of corporate political action committees will be at least as great over the next few years as that of the Moral Majority. He portrays the new crop of conservative Senators and Congressmen who were elected with millions of dollars in corporate aid as “people who are not only indebted to corporate contributions, but more than that, who have corporate models internalized, who themselves act as nearly as they can in politics like middle management in corporations.”

Corporate money will also become more important outside politics as other sources of funding disappear. First, the Government will become tighter with handouts. Richard Cyert, president of Carnegie-Mellon University, predicts that science-oriented colleges will lose money for basic research at one end, but gain it back in defense contracts (often directly tied to corporations) at the other; liberal arts colleges will simply lose. Second, foundations will continue to be weakened by a 1969 law requiring them to pay out all of their earnings each year to the Government thus preventing them from building their endowments to match inflation. That means that cultural, educational and civic organizations will have to rely increasingly on business support. Corporate managers will gain influence outside the traditional corporate bailiwick.

How then to make sense of these two contradictory trends in power? Governor Jerry Brown argues that the “tension between the periphery and the center, between the hick and the city slicker” will be the – fundamental power conflict of the 1980’s. And the people who shape the future may be those in the middle. People like Camille Haney in Chicago, who brings together corporations and consu-merists and gets them to compromise. Or like Federal Appeals Court Judge Amalya Kearse. (Ralph Nader predicts that the Federal courts, now dominated by Carter appointees, will become the chief battleground for public-interest groups). People like Brown himself, who seems to root for those on the peripheries of power while aiming for the center. Or like Reagan, who can simultaneously appeal to the localists and to the multinational corporations. Perhaps it will be that ability—to seem a part of the old and the new, the center and the periphery, and to mediate between the two—that will be the crucial quality for those who would wield power in this country’s future.

—Richard Connrff