His fuel of the future can be drawn from your faucet

By Kenneth Jon Rose

January 1982

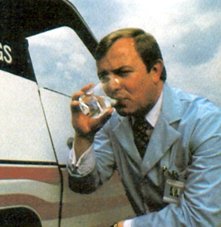

In Missouri there’s a man who likes to drink his car’s engine exhaust in front of company. He sips slowly, relishing its flavor as if he were sampling fine wine. Then he passes it around to his wide-eyed guests. Most of them politely decline the offer, but there’s always someone curious enough to taste it. Anybody who does is amazed at the discovery “It’s water!” the person exclaims. “Plain, ordinary water!”

That’s usually the reaction Roger Billings gets when he offers his guests a sip of exhaust from his hydrogen-fueled car. It’s been that way ever since he converted his first car to hydrogen when he was sixteen years old. Since then he’s converted just about every kind of engine, from car engines to tractor engines, to run on hydrogen. He’s even built, and lived in, a hydrogen-powered home.

Billings is a man with a vision. He sees hydrogen as the fuel of the not-too-distant future, and he’s been spending his time and energies coming up with a technology that makes it easier to use, whether for fueling the vehicles we drive or heating our homes or generating electricity.

At the age of thirty-three, Billings is a director of the International Association for Hydrogen Energy, an organization that includes some of the top hydrogen researchers in the world, and he’s the president, chairman of the board, and director of two corporations: Billings Computer Corporation and Billings Energy Corporation.

Fresh out of college with nothing more than $400, he formed the Billings Energy Corporation in 1972. At the beginning it had only one employee: himself. Today it employs more than 250 people, including George Romney, a former governor of Michigan and former head of American Motors Corporation.

In its short life the Billings Energy Corporation has become one of the most respected and most successful hydrogen-technology companies in the United States –so successful that several oil companies have tried to buy it, without any luck. “We want our technology to be bought, but we don’t want to be bought,” Billings says. “Roger Billings and his little crew of creative people are just not for sale.” Since he built his first hydrogen-powered car, Billings has nurtured a dream of seeing the United States become energy independent. The fuel that’s going to give us that independence, he’s convinced, is hydrogen. He has been devoting his expertise, and the profits from his computer corporation, to bringing that about. His is a fervor that impresses his colleagues. “We see hydrogen as a fuel for the distant future. Billings sees it as being used more immediately,” physicist Walter Stewart says. Stewart is a hydrogen fuel expert at Los Alamos Laboratory, in New Mexico.

As a future fuel, hydrogen has a lot to offer. It’s the most abundant element in the universe. On Earth it is mostly bound up in water, which makes it almost inexhaustible. It’s also highly efficient. It produces more energy per pound than fossil fuels do. Best of all, hydrogen can easily be substituted for natural gas, diesel fuel, and gasoline.

“Hydrogen is not a fuel

you convert a home to. It’s a system you

convert a community to.”

Up to now the greatest problem has been how to store it. Once it could be put only into a pressurized bottle in its gaseous form, or cooled to -253°C (-423°F), at which point it becomes a highly explosive liquid. But in the last 15 years there’s been a breakthrough in what are called hydrides, metal alloys that absorb hydrogen gas the way a sponge does and release the gas when they’re heated. Both the safety and the limitations on the amount of gas that can be squeezed into a container have been improved so that it’s now possible to build hydrogen-fueled vehicles.

While just a high-school senior, Billings converted his father’s old Model A Ford (“he wouldn’t let me touch his new Chevrolet”) to run on hydrogen. That feat won . him the Gold and Silver Award at the 1966 International Science Fair, in Dallas, Texas, and a scholarship. His fascination with hydrogen continued when he studied systems engineering at Brigham Young University, in Utah. While there, he continued his work on hydrogen technology with a grant from the Ford Motor Company.

Today much of that has paid off in the work he’s done on hydrogen vehicles. One of his pet projects has been to take a compact car, a Dodge Omni, and make it a two-fuel car that can use either gasoline or hydrogen. In addition to a regular gas tank, it has a hydride tank specially designed by the engineers at the Billings Corporation. About the size of a spare tire, it fits snugly under the trunk and has enough fuel capacity to take you about 100 miles.

To make you go farther, Billings installed a simple switch on the car’s dashboard. Flick it one way and you’re driving on gasoline. Flick it back and you’re on hydrogen again. Billings made the cars dual-fueled for the simple reason that it’s tough to buy hydrogen at your neighborhood service station. “If a driver happens to go on vacation, he’s got to have some other fuel. So this is a way of being able to get one foot in the door with-out converting the whole world,” he explains. So far he’s converted ten automobiles to his dual-gasoline-hydrogen system.

As a car fuel, hydrogen can’t be excelled. It’s clean, and the engine also wears better. “The gasoline engine,” Billings says, “operates at almost the same efficiency on methane, methanol, or gasoline. But when you convert the engine to run on hydrogen, you get a forty percent boost in efficiency.” The Environmental Protection Agency rates the Omni’s overall fuel economy at 30 miles per gallon of gasoline. The hydrogen-powered Omni averages 44 miles per gallon and can hit a top speed of 80 miles an hour.

Billings plans to sell his two-fuel Omnis to anyone willing to pay the steep $30,000 price tag. After the first 10 have been tested out in the marketplace for a year, he hopes to build 100 more, at less than half the original price. In the meantime he’s designing conversion sets for those who want to change their engines to run on hydrogen. The kits might be out by the mid-1980s.

Meanwhile the news has got around that what Billings does, works. “We have a lot of people who write us letters, saying, ‘I want to convert my car today. I want to convert my helicopter, my boat. How much will it cost?'” He’s even been contacted by the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, asking him to help convert the engine of a Buick Century so it could run on hydrogen fuel.

Billings has designed a ready source of at-home hydrogen. When the driver wants to refuel, he simply connects his car to a Billings electrolyzer. Overnight the unit splits water coming from the tap and pumps hydrogen into the tank. By morning he’s ready to go. But-making hydrogen with house current is expensive —more expensive in most places than getting gasoline at the pump. That would change if the country converted to a hydrogen economy.

Today the most exciting break in hydrogen technology might come from solar-energy research. For instance, at the third International Conference on Photochemical Conversion and Storage of Hydrogen Energy, sponsored by the Solar Energy Research Institute (SERI), scientists announced that it may soon be possible to produce hydrogen from sunlight.

For example, Nobel Prize-winning chemist Melvin Calvin, from the University of California at Berkeley, announced that he had developed a synthetic chloroplast, a man-made copy of the part of the plant cell that is responsible for photosynthesis, converting solar energy into stored energy in the form of a sugar, glucose.

In nature, the plant chloroplast uses the energy of sunlight to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. The hydrogen then fuses with carbon dioxide from the air to build carbohydrates, and oxygen is set free into the atmosphere. In Calvin’s design, the man-made chloroplast produces molecular hydrogen instead of carbohydrates. Calvin has a way to go before his process can be used commercially, but solar experts are convinced that he, or someone equally ingenious, is going to come up with a system that will effectively extract hydrogen from water, using sun power. One SERI official adds, “We’re almost there.”

Billings stands beside one of his hydride tanks, able to hold 63 pound of hydrogen.

Meanwhile Billings has grand energy plans of his own. With the help of an old technology, he hopes to make this country totally energy independent by the turn of the century. Billings calls his master plan for this self-sufficiency Project Liberty.

A sort of modern-day Manhattan Project, Project Liberty is Billings’s answer to OPEC. Since we have vast coal reserves in this country, Billings wants to build coal-gasification plants to change coal into hydrogen. The 40 coal-gasification plants now operating throughout the world make only synthetic natural gas, with hydrogen as a by-product. Not only is it more energy efficient, Billings says, to gasify coal into hydrogen, but it’s also cheaper.

By the year 1990 this hydrogen-minded Johnny Appleseed wants to sprinkle the country with enough coal-gasification plants to offset all foreign oil imports. He figures that it will take 50 hydrogen plants to replace just the gasoline made from imported oil and that another 50 will be needed to eliminate foreign oil imports completely by the year 2000. “We could do it faster than that. And I’m unhappy to say,” he adds, “that we could have done it at least ten years ago.”

The U.S. government bears much of the blame for frustrating Billings’s dream. There is a tinge of bitterness in his voice when he talks about the Department of Energy. “The DOE is a joke. It really is,” he complains. “Government research is so much less efficient than industrial research. If a company were to spend money like that on research, it would go broke. When I see all those resources wasted, it really, really bothers me.”

Other nations, however, are more enlightened. India has established a Hydrogen Energy Task Force as part of its governmental effort to reduce oil imports. Japan is planning to produce commercial hydrogen; first it will use nuclear energy in the 1980s, then solar energy in the 1990s. West Germany already has hydrogen-fueled buses in service in both Stuttgart and West Berlin, and the West Germans are involved with newer hydrogen technology as well. Three years ago the West German government sponsored an international symposium on hydrogen in air transportation, at which aerospace experts discussed developing a small fleet of hydrogen-fueled wide-body jets.

Not one to be easily discouraged, Billings is not waiting for our government to get going. In 1980 he moved his corporation from Provo, Utah, to Independence, Missouri, to begin Phase 1 of Project Liberty: a hydrogen-powered community. He is in the process of changing 20 homes and 100 vehicles in Independence to run on hydrogen. Even the mail delivery vehicles, donated with the blessing of the U.S. Postal Service, will be hydrogen-fueled. Since there isn’t any coal-gasification plant in Independence, his company is going to supply the city with hydrogen by piping it in from firms in the area that produce the gas as a manufacturing by-product.

Billings is modeling the homes after the one he and his family lived in for two-and-a-half years before they moved to Missouri.

Everything in it, from the hot-water heater and the barbecue to the garden tractor and the family car, ran on hydrogen.

A computer system that the Billings Computer Corporation manufactures monitored the hydrogen production and storage as well as the inside controls for heating and cooling and even the security of the place. Besides the 19 homes he is converting in the community, Billings is building a new hydrogen home for himself; this is not something he recommends to the individual homeowner. “Hydrogen is not a fuel you convert a home to,” he says. “It’s a system you convert a community to.”

Project Liberty is a small step in that direction. His next project is a wholly hydrogen-powered town in Iowa. A few years ago the town leaders of Forest City, Iowa, heard of Billings’s work. They wanted some kind of inexpensive energy alternative. They couldn’t produce their own electricity because the town’s generating plant needed expensive, hard-to-get diesel fuel. Their only alternative was to buy the electricity they needed, at high rates, from another utility system. They told Billings about their situation. He went in and looked the place over and decided to build his first Project Liberty coal-gasification plant in their town.

Iowa coal is so cheap that Billings estimates it would be the equivalent of producing gas at 50 cents a gallon. The hydrogen-fueled plant is expected to provide all the industrial and domestic electrical needs of Forest City’s 4,000 residents and still have power to spare to heat every home there and to fuel every car. Billings is confident that his plant is going to be up and operating by 1984.

Further in the future he has grander hydrogen dreams: a mammoth hydrogen/electrical complex, where he will gasify coal and pipe it to facilities 2,000 miles away, and another large plant he wants to construct in southern California.

There he envisions a hydrogen-powered Los Angeles: a city that has no energy shortages, no gasoline lines, and, ultimately, no smog. —

For Further Reading:

Bova, Ben, “Hydrogen Fuel,” The High Road, Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1981.

Escher, W, “Hydrogen Energy: Readying a New Energy Option,” Technology Tomorrow, Vol. 2, No. 2, April 1979.

Hydrogen Progress, Billings Energy Corporation, 18600 East Thirty-seventh Terrace South, Independence, MO 64057.

The International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, official journal of the International Association for Hydrogen Energy, P.O. Box 248266, Coral Gables, FL 33124.

“Light Cleaves H2S: A Profitable Split?” Science News, Vol. 120, No. 10, September 5, 1981.

Copyright © 1982 Omni. All rights reserved.